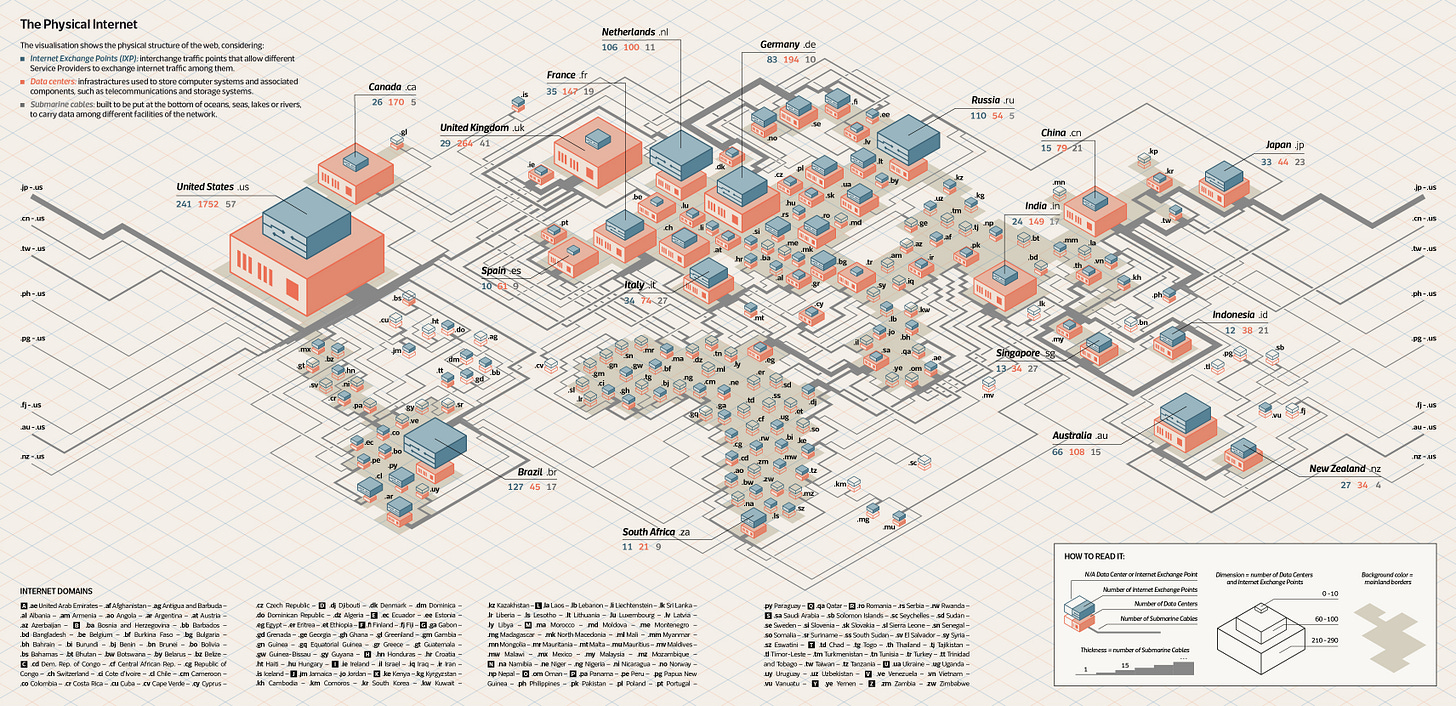

Vast (and vulnerable) submarine fiber-optic cables, unassuming data centers, cages and closets, backup generators and penetration testing, IXPs, even the rhythmic nature I hear in the term commodity servers.

Silicon wafers, state-of-the-art climate control.

Chokepoints.

Bottlenecks.

I’m intrigued by internet infrastructure.

Not because it gives me that thrill of behind-the-scenes insight like bonus footage on a DVD, and not because I’m the kind of person who likes to harbor nifty little factoids (unless, of course, it’ll help me solve a crossword). Nor do I truly think IT infrastructure could ever truly be “sexy.”

Rather, what really gets me going about the physical infrastructure of the internet is that it’s tangible, it’s visible, and I can see it. To me, this really brings the whole thing down to earth. I can’t see the real 0s and 1s, I can’t see radio waves or data transfer. But I can see a data center and servers and even a cross-section of fiber-optic cable.

This feg explains why I somewhat thrived in high school biology and totally aced geology, but barely passed chemistry and was given a school-sanctioned pass even dumb (I mean, remedial) physics.

I can’t see protons or neutrons, I can’t see the space-time continuum or the weight of gravity. But a strata of rock? A ribosome? I can see them, even feel them!

The internet and computers in general always felt so out of reach for me. Sure, I’ve been a computer user since the tender age of three when my dad bought a Macintosh and a surfer of the world wide web since the days of dial up … but beyond the bounds of the personal computers, the web, and other increasingly user-centric interfaces, I’ve never felt like understanding the nuts and bolts of it was open to me.

A sort of “There, there now, pet” somehow permeated from my devices and ethernet cables. Like the wife of a slain millionaire in my Agatha Christie novel of the week.

“Have you any knowledge of what the business in Buenos Ayres was?”"

“No, monsieur, I know nothing of it’s nature.”

In The Murder on the Links, Madame Renauld was expected to fully use and reap the benefits of her husband’s great business and fortune, but only enough to the point that she could take advantage of it. What went on inside it was a man’s business!

As a direct beneficiary of the personal computer revolution and the invention of the user-friendly world wide web, I feel Mme. Renauld. I literally used to sell cloud-based software for a living and new nothing of its nature.

And while I don’t want to use a command line any more than the next person, it’s true that GUIs, PCs, and the web have abstracted what’s going on underneath. And in the knowledge of that underlying infrastructure holds a lot of power.

I admit, I was never particularly interested to know what went on inside my PC or how AOL actually worked. That’s partly my age at the time and my nature and interests in books and dolls, but I’m sure I absorbed the male-oriented, math-person edge that all things computer science took on in the 80s and still has yet to fully shed.

As NPR writes, in the 80s and 90s, “This idea that computers are for boys became a narrative. It became the story we told ourselves about the computing revolution. It helped define who geeks were, and it created techie culture.”

While I was glad to get a pass on physics (not required to graduate in NY state), I’m left with the feeling that the school might have pushed me to apply myself a little more to stick with it and see it through if I’d been a boy.

Because now, more than a lifetime later, not only have I learned all this abstract, often invisible and virtual computer and cloud stuff I unconsciously assumed was off limits to a girly girl like me … I’ve largely taught it to myself!

Beyond just being able to see it, the visual representation of buildings and data centers and internet exchange points makes the internet much more tangible to me than a screen of 0s and 1s and whatever the internet amounts to in our heads.

Plus, the web and cloud boiled down to a bunch of nondescript buildings full of racks of servers and unsightly primary-colored wires? It’s so the opposite of the third-wave coffeehouse aesthetic of the internet today. Which, if you’ve conversed with me lately, you know I’m growing increasingly weary of.

Beyond the boost to my own comprehension of the whole system the physical internet provides me, as well as the slight schadenfreude I take in a fissure in the seamless, millennial internet of dreams, upon reflection - and perhaps I say this somewhat gleefully - the physical internet underscores for me a certain fallibility about the whole thing.

Rubbery cables on the sea floor. Non-descript, earth bound buildings. Servers built to withstand the atmosphere of outer space, but no less resistant to a baseball bat than a mobster on the wrong side of Tony Soprano.

I saw what happened to all those computers at the end of Office Space.

The thing I relish in with physical internet infrastructure is that it’s a reminder that the internet is a thing, and things are susceptible to both man-made and natural nuisances and disasters, from trawlers to gas explosions to frozen pipes, just like train stations and lighthouses.

It’s a reminder that the internet is propped up not by the gods, but by largely by telecoms giants, government agencies, real estate agents, and perhaps more rogue actors than we might like to admit.

And I suppose the “murderino” in me finds this titillating in a way similar to how I felt about an impending Y2K or a CDC-inspirted zombiepocalypse. It’s all just teetering on the edge a bit, isn’t it?